Ī French translation appeared 1850 in Paris in Hermann Ewerbeck's book Qu'est-ce que la bible d'après la nouvelle philosophie allemande? ( What is the Bible according to the new German philosophy?). In parts of the book, Marx again presented his views dissenting from Bauer's on the Jewish question and on political and human emancipation. Then, in 1845, Friedrich Engels and Marx published a polemic critique of the Young Hegelians titled The Holy Family. In it, he responded to the critique of his own essays on the Jewish question by Marx and others. From December 1843 to October 1844, Bruno Bauer published the monthly Allgemeine Literatur-Zeitung (General Literary Gazette) in Charlottenburg (now Berlin). "Zur Judenfrage" was first published by Marx and Arnold Ruge in February 1844 in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher, a journal which ran only one issue. Having thus figuratively equated "practical Judaism" with "huckstering and money", Marx concludes, that "the Christians have become Jews" and, ultimately, it is mankind (both Christians and Jews) that needs to emancipate itself from ("practical") Judaism. Thus, the Jewish religion does not need to disappear in society, as Bauer argues, because it is actually a natural part of it. This is the starting point of a complex and somewhat metaphorical argument that draws on the stereotype of "the Jew" as a financially apt "huckster" and posits a special connection between Judaism as a religion and the economy of contemporary bourgeois society.

In response to this, Marx argues that the Jewish religion does not have the significance Bauer's analysis attributes, because it is merely a spiritual reflection of Jewish economic life. Hence, to achieve freedom by renouncing religion, Christians would have to surmount only one stage, whereas Jews would need to surmount two. In Bauer's view, Judaism was a primitive stage in the development of Christianity.

Bauer states that the renouncing of religion would be especially difficult for Jews. In the second part of the essay, Marx disputes Bauer's "theological" analysis of Judaism and its relation to Christianity. As noted above, political emancipation in a modern state does not require Jews (or Christians) to renounce religion only complete human emancipation would involve the disappearance of religion, but that is not yet possible "within the hitherto existing world order". In Marx's view, Bauer fails to distinguish between political emancipation and human emancipation.

#Carl marx general thoughts free#

Marx concludes that while individuals can be "spiritually" and "politically" free in a secular state, they can still be bound to material constraints on freedom by economic inequality, an assumption that would later form the basis of his critiques of capitalism.Ī number of scholars and commentators regard "On the Jewish Question", and in particular its second section, which addresses Bauer's work "The Capacity of Present-day Jews and Christians to Become Free", as antisemitic however, a number of others disagree. On this note, Marx moves beyond the question of religious freedom to his real concern with Bauer's analysis of "political emancipation". The removal of religious or property qualifications for citizens does not mean the abolition of religion or property, but only introduces a way of regarding individuals in abstraction from them. In Marx's analysis, the "secular state" is not opposed to religion, but rather actually presupposes it. Marx uses Bauer's essay as an occasion for his own analysis of liberal rights, arguing that Bauer is mistaken in his assumption that in a "secular state" religion will no longer play a prominent role in social life, and giving as an example the pervasiveness of religion in the United States, which, unlike Prussia, had no state religion.

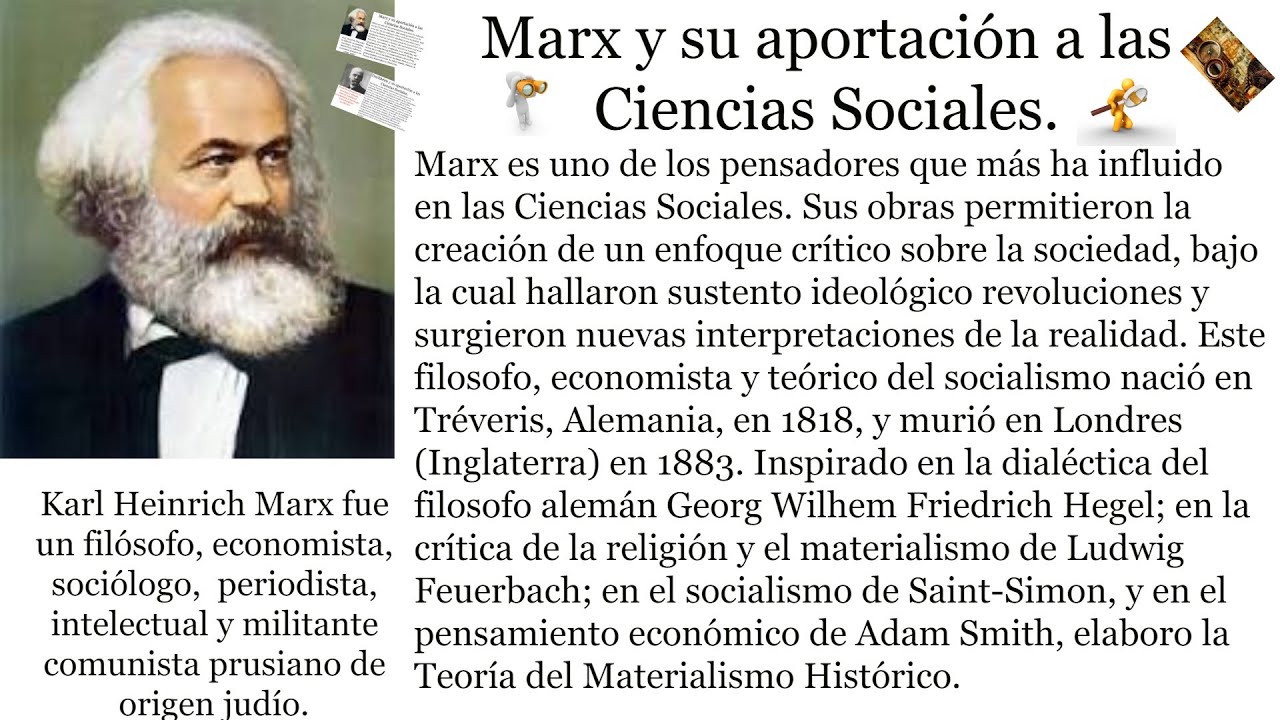

True political emancipation, for Bauer, requires the abolition of religion. According to Bauer, such religious demands are incompatible with the idea of the " Rights of Man". Bauer argued that Jews could achieve political emancipation only by relinquishing their particular religious consciousness since political emancipation requires a secular state, which he assumes does not leave any "space" for social identities such as religion. The essay criticizes two studies by Marx's fellow Young Hegelian Bruno Bauer on the attempt by Jews to achieve political emancipation in Prussia. Marx wrote the piece in 1843, and it was first published in Paris in 1844 under the German title " Zur Judenfrage" in the Deutsch–Französische Jahrbücher. " On the Jewish Question" is a response by Karl Marx to then-current debates over the Jewish question.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)